- Home

- Our Community

- Our Faith

- Parish Life

- Bulletin

- Contact Us

- Search

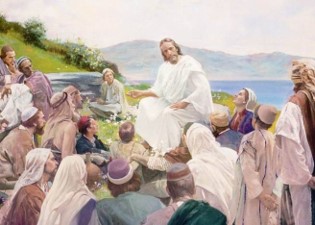

4th Sunday Ordinary Time - Year A

The proclamation of the Gospel on this Sunday and the next will reacquaint the praying assembly with the Great Sermon and its challenges. Although these challenges lie at the heart of what it means to be Christian, too few of us believe that it is possible to live them out in the context of the daily grind. Many have attempted to do so – Dorothy Day, Henry Nouwen, Daniel Berrigan, Oscar Romero, Charles de Foucault, Dom Helder Camara, Mother Teresa of Calcutta, to name a few. But more often than not, these have become the exceptions whose absolute adherence to the Sermon’s precepts has led them to be labelled as extremists or fanatics, too radical for the “mainstream Christianity”.

“Getting on with it” will require that we be fired by a spirituality that finds blessedness in humility and strength in obedience. In today’s first reading (Zeph 2:3, 3:12-13), the prophet Zephaniah holds out to us as an example the anawim or remnant or poor ones who rely solely on God. In their humble reliance, they may seem weak in the eyes of the world, but they are building their houses on rock. Zephaniah’s description of the poor ones anticipates the spirituality set forth in the Beatitudes (Gospel, Mt 5:1-12) that will introduce the Great Sermon.

These statements of blessedness, explains C. Milo Connick (“Jesus, the Man, the Message and the Mission”, NJ; 1974), describe the character of the members of the kingdom of God – the followers of Jesus in any age. It is significant that both Matthew (5:1) and Luke (6:17) made it clear that the Beatitudes and their challenge were directed toward Jesus’ disciples who had already opted to make Jesus’ way of life their own. By virtue of that option, grace was available to them, grace that made the spirituality of the Beatitudes possible and practicable.

Whereas some may suppose that the Beatitudes are requisites necessary for entering the kingdom, they are actually the resulting dispositions of those who have already, and by grace, opened their hearts and minds to put on the heart and mind of Jesus. These are not candid camera shots of eight different kinds of character; rather, they represent one character in eight different ways, like so many facets of a diamond. The character described is, of course, Jesus Christ, and the verbal portrait is itself an invitation not only to do what Jesus did but to become Jesus for the world.